In response to the higher prices some consumers will switch to other products which are cheaper but less preferred. This is transferred to producers as economic rents/monopoly profits. In addition, the higher prices mean that consumers lose some of the benefit of transacting in the market, that is, consumer surplus decreases. Additionally, a monopolist is likely to be x-inefficient. If the unit cost of production decreases as output increases, this will be production inefficient.

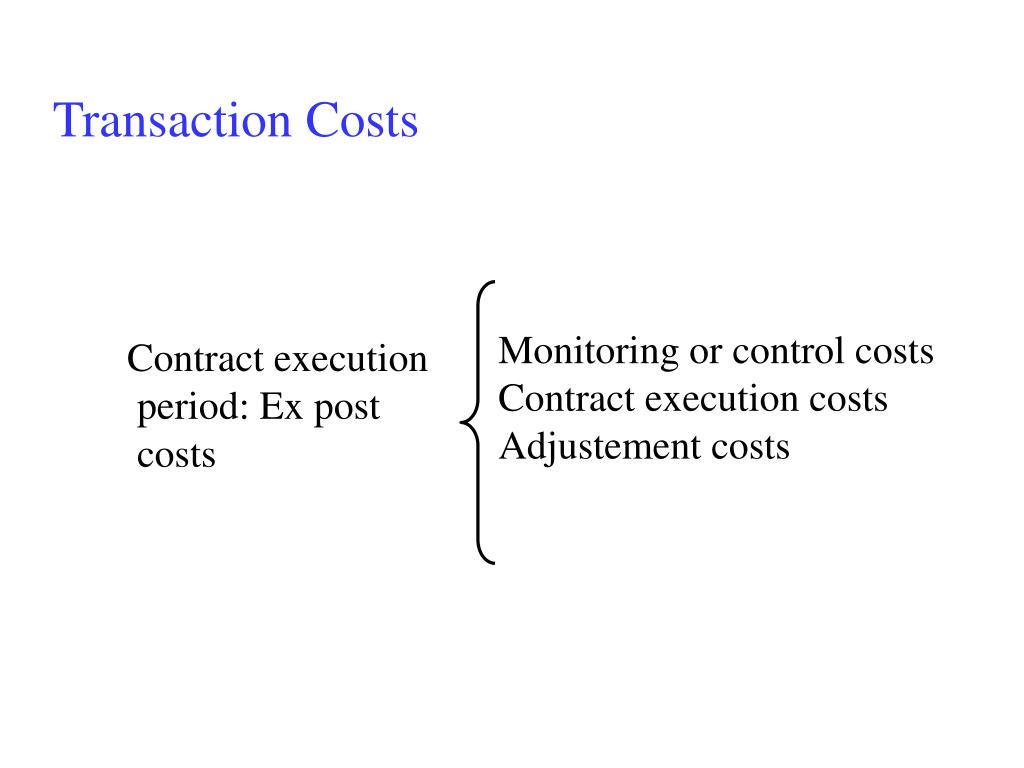

The lack of competition means that producers are able to restrict output and charge a price above the economic cost of production (which includes return to capital). Markets that are not very competitive tend to be relatively inefficient. Conduct that caused the exit of that firm or even curtailed its ability to compete effectively could damage the competitive process However, an entrant into a market may be production inefficient even though once it becomes established it may be more efficient than incumbent firms because, for example, it has a better product or better technology. Given this, only conduct that excludes or deters firms that are at least equally as efficient as the firm engaged in the conduct is likely to contravene competition law. The exit of these firms enables resources to be reallocated to other firms that will better serve the market. They will incur higher costs than their rivals and so will be priced out of the market or they may not be supplying product of a quality or variety that consumers want. This will have the effect of lowering the long run average cost curve but additional costs associated with this may increase costs in the short run, representing a tension between short run and long run gains.Ĭentral to competition policy and law is the acceptance that in competitive markets inefficient firms will not survive. Dynamic efficiency may also be increased by the introduction of better work practices. Consequently, it is closely related to R&D and innovation. However, despite recognition of the significance of transaction costs, this is not a unanimously accepted view.ĭynamic efficiency is an assessment of how quickly and completely firms adjust to change, whether on the demand side, such as a change in consumer preferences, or on the supply side, such as the adoption of new cost-saving technology. Arguably, ensuring that the organizational structure of a business minimises these costs is a form of efficiency. Decisions about whether to source inputs from the market or to self-supply are at least in part a reflection of these costs – high transaction costs provide an incentive to self supply. They include the cost of monitoring, controlling, and managing transactions. Transaction costs, as the name implies, are costs that arise when making a sale that are additional to the cost of production. Together, production and allocative efficiency are static measures as they are assessed at a point in time and so assume that key variables such as technology are given. Firms will be allocatively efficient when consumers willing to pay a price at least equal to the marginal cost of producing the product obtain supply. The cost differential reflects the firm’s ability to ignore at least to some degree market pressures, that is, its market power.Īllocative efficiency refers to how well resources are allocated between productive activities in order to best satisfy consumer preferences. An example would be the ‘gold plating’ of the CEO’s office suite.

A related concept is x-inefficiency which measures cost incurred by a firm in excess of that which would be incurred in a competitive market. Production efficiency (also referred to as technical efficiency) occurs when a firm produces a given output at the lowest unit cost of production given the technology employed. There are various different aspects of efficiency. Economic efficiency is a measure of how well a market or the firms within it are performing.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)